When The Unconformity team starts planning each version of our biennial festival, the task is so monumental that it’s as if our palms rest upon a giant, immovable boulder, its composition and shape indistinct. Over time, as we conceive ideas, make plans and set our course, that great weight gains definition and we manage to inch it forward.

A growing cast of artists, community members, volunteers, partners and crew join the team, and every action and conversation helps guide the festival along its path. Time seems to stretch and then rapidly condense. Before you know it, the festival dates arrive and hundreds of hands roll the boulder forward: a crashing conglomeration of people, art and place.

At 3:13pm on Friday 15 October 2021, we made the heartbreaking decision to cancel The Unconformity festival on its opening day due to a snap lockdown in southern lutruwita/Tasmania. If you look deeply at who we are and where we have come from, you realise that we had no choice but to stop that sparkling boulder in its tracks.

We first held this festival, in regional western lutruwita/Tasmania, in response to community desire and need. Via a survey, West Coast locals told us—a grassroots committee called Project Queenstown—that the town needed a festival. None of us had worked on a festival before. We held a community meeting in the old West Coast Council chambers and it was decided that this festival would focus on art, culture and heritage. There were about 30 people in the room, overlooked by portraits of former mayors and wardens of the West.

From this basis, we birthed the first Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival, which was held in May 2010.

In those early days, one of the best decisions we made was to set a biennial cadence to this event. Wise heads around the committee table knew that our group of volunteers and our community would best rally around a local festival every two years. Looking back, even then we knew that creating something ambitious, in a place that had few roadmaps for such activity, had a cost.

Instinctively we knew that the festival should be specific to and resonant with the social, environmental and industrial circumstances of Queenstown. We went down the path of conceiving and creating our program, not knowing that a commission-focused curatorial model was unusual—or that there was an alternative approach.

Barely any photographs exist of our first festival because we didn't think to organise a photographer.

Two years later, we decided to link the second Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival with the centenary of an event that is imprinted in the living memory of Queenstown. In October 1912, 42 men perished due to a fire in the North Mount Lyell mine with the fatalities increasing to 43 when one of the heroes of the rescue efforts, Albert Gadd, subsequently passed away from carbon monoxide poisoning.

The 50 activities comprising that second event included commemorative services, dedication plaques, book launches and sculpture reveals alongside contemporary art installations, exhibitions and public performances. I wept with many others as 42 kids carried illuminated, self-made lanterns down the town's iconic main street and placed them on a re-creation of the funeral train carriage. The train's whistle piped strong into the night and the carriage departed slowly, while on a nearby balcony a soprano sang Nearer My God To Thee. That night, ‘the arts’ was a powerful vehicle through which to explore community memory and mourning and the complexity of standing at the foothills of mountains that have both provided and taken so much from us.

In 2014, another centenary provided the conceptual focus for that year’s festival. Located around ten kilometres outside of Queenstown, the historic Lake Margaret Hydro-Electric Power Station celebrated 100 years of renewable operation. Various screen, sculpture and performance works were installed at the power station itself, in the shadow of Mount Sedgwick. Back in Queenstown, the kinetic forces of industry were projection-mapped onto the streetscape, bringing turbines into the heart of the community to reframe and animate public space.

The entwined nature of art, community and wellbeing came to the fore during that festival. In late 2013, three Queenstown men lost their lives in the local mine—incidents that shook the foundations of the town. The mine subsequently closed and hasn't reopened. Nearly ten months later, our festival program acknowledged what the town was going through:

Since our last festival, Queenstown has lost lives and livelihoods at Mount Lyell. The grand old mountain is showing signs that she has had enough, as we dig deeper and pry further into her mineral-rich underbelly to provide the lifeblood for our community. For more than 100 years, Mount Lyell has given up her wealth without question. Is she finally telling us she has no more to give? Are the naysayers right? Is our historic mining town really dying with her?

Not on your nelly! There's still life and hope in those hills. And something even stronger and more unique in the valley below—a spirit that has endured and thrived during more than a century of isolation, rampant weather and the trials and tribulations of the mining industry.

The opening event for the 2014 festival involved The Angel of the West, a symbol for the town's collective trauma and grief. West Coaster Alex Crosswell, then 14 years old, stood before a large crowd to acknowledge that while the town was hurting, we would rebound, we would survive, as unplanned flames licked at the angel's face.

Those early festivals were both exhausting and exhilarating. In hindsight, they shouldn't have existed. The workload on everyone involved was incredibly high. A core team of people gave a hell of a lot to the idea that an old mining town can think and act creatively, expansively and inclusively.

In 2015, after six years of working on the Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival, we felt the urge to grow and renew.

Our attention turned to deeper, intangible concepts: how polarising concepts like boom and bust, acceptance and rejection, risk and conservatism, hope and despair, all lie in the bones of our landscape and our history; how 'conventional' ways of doing things are often rejected; how the West Coast both confounds and seduces through being so inalienably different to everywhere else; how it does not conform.

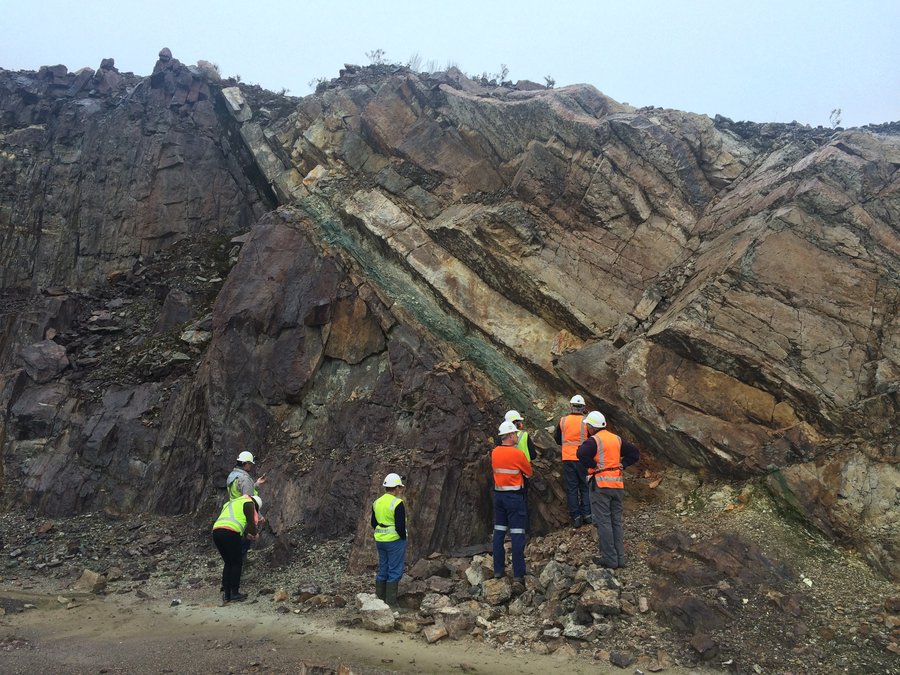

I remember talking to our then-chair Joe Gaspersic. We discussed how The Haulage Unconformity geological fault at Mount Lyell could be an allegory for these ideas, the incongruous folds of earth representing the paradoxical qualities of Queenstown. Joe revealed that The Haulage Unconformity is best seen at a quarry that he owned at Mount Lyell; connections and coincidences run deep on the West Coast.

In September 2015, we announced The Unconformity at a gala fundraising event in The Paragon Theatre in Queenstown:

What is The Unconformity?

It's an immense geological asset up at the Mount Lyell mine site—our most significant asset. It's a discord in our local geological identity.

The Unconformity, we feel, is our spirit of place. It's a feeling of a singular sense of identity. We don't conform, we march to the beat of our own drum and that's what makes us special; that's what makes us unique.

It's rejoicing being on the fringe, at the bottom of the world together, in Queenstown.

It's a loud new voice for Queenstown, spreading from the West Coast across lutruwita/Tasmania, and it's spreading nationally.

It represents us changing the narrative to how the West Coast can provide leadership; how the West Coast can benefit lutruwita/Tasmania.

The Unconformity is the reimagining of our festival. It's our new name, and it's happening in October 2016.

We set our sights on prospecting new cultural terrain alongside our community. We embraced big opening ceremonies, experimental sound, live art and performance. An art trail linking audiences with local artist studios and exhibitions became central to the festival experience. An ambitious array of artistic projects were produced for the 2016 and 2018 festivals: a human-sized cake replica of the mountain; a limestone quarry transformed into a giant singing bowl; an 8.8-tonne boulder dispersing shockwaves through the streets; sculptural barbecues fashioned in local workshops from underground mining machinery; contemporary dance within the orange sulphuric waters of the Queen River; a performative train journey through ‘the geology of grief’; and audio-based theatre presented underground in a disused mine.

Over time, The Unconformity has developed other initiatives which include funded artist residencies, youth arts programs alongside Mountain Heights School, funding to support local cultural groups and artists, a screen-based live stream experiment, an online publishing platform, a story-based smartphone app, and a program that supports the commissioning of visual art by local artists. Working with key people from the Aboriginal community of lutruwita/Tasmania, we have invested in a number of cross-cultural and Aboriginal-led programs. Most prominently, a funded and non-outcome-driven residency for an Aboriginal artist or cultural practitioner that encourages reciprocal engagement with the West Coast community.

The Unconformity now operates in a rapidly-changing social and cultural ecosystem. Creative energy has drawn new residents who value difference and a welcoming community. West Coast visual artist, Raymond Arnold, recently termed Queenstown an 'art mining town'—a significant marker for a place that, for so long, has been locked into its past. In this context, The Unconformity now represents a concept or idea rather than just a festival: as modern Queenstown grows and changes, so too must we change.

On 15 October 2021, on the opening day of The Unconformity 2021 festival, the Tasmanian Premier announced that municipalities in southern lutruwita/Tasmania would enter a snap three-day lockdown due to the potential of widespread community transmission of COVID-19.

We, like many others, had an early indication that the lockdown was in motion. Our core staff and crew came together and, with a representative from Events Tasmania in the room, discussed the viability of the festival with over 50% of the population of lutruwita/Tasmania in lockdown.

Well over 1000 people were travelling to the festival from southern lutruwita/Tasmania that weekend. Each of these people had the unknown potential of bringing COVID-19 along the Lyell Highway and into the vulnerable West Coast community. This had a domino effect upon the internal systems and structures that underpin the festival, compounded by the reality that somebody could contract COVID-19 at the festival; a community member, volunteer, staff, crew, artist, or local or visiting attendee.

Events that are operating in this volatile era need to have plans in place to deal with situations caused by COVID-19. They also need to take on the responsibility to cancel, if the situation demands it. With 1090 days having passed since the last day of the 2018 festival, the decision to cancel the 2021 festival was heartbreaking. It impacted artists, staff, audiences, food vendors, venues, accommodation providers and other local businesses who were laser-focused on maximising revenue from the festival weekend.

Subsequently, the Tasmanian Government offered a West Coast Business Support Grant to businesses who were impacted by the festival cancellation.

Following the cancellation, the town chose to kick on and the independent nature of the festival's art trail shone forth, with venues and artists and exhibitions proudly engaging the remaining public. What we glimpsed on that weekend was The Nonconformity: the outline of a festival, minus the dazzling energy that can only spark into being when the holistic package comes together.

The act of stopping a festival in that last-gasp moment can only leave collateral damage. The boulder threatens to roll over the top of you before coming to a stand-still. The human cost of putting on these events is well known in the industry but may not be understood more broadly. I'm incredibly proud of how everyone pulled together to support each other and un-produce something that had taken years to produce, that only moments earlier they had collectively been creating.

As a general rule, we don't often look backwards as an organisation, but it's important to remember that before The Unconformity there was a Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival, and before that there was a Project Queenstown committee, and before that other committees with other names stretching way back to our genesis in Queenstown in 1984. This organisation's roots are sewn in the West Coast community and The Unconformity stands on the shoulders of the hard work conducted by countless people on the ground.

We would not risk making a decision that could jeopardise the safety of this community. Together, with a gargantuan effort, we stopped the boulder in its tracks, with the knowledge that we’d roll it again someday soon.

Travis Tiddy

Travis Tiddy is a third-generation Queenstown person who is deeply invested in an arts-led revival of his community. He is the founding director of the biennial Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival and now the Artistic Director of The Unconformity.

Header photo by Rémi Chauvin